The George Economou Collection is pleased to announce The Giddy Road to Ruin, the first survey exhibition by German-American artist Charline von Heyl (b. 1960) in Greece.

Across three floors of gallery space, The Giddy Road to Ruin will feature select works from the last several decades. The earliest is an outstanding painting from the George Economou Collection—an emblematic example of the artist’s practice—Untitled (11/93, I) (1993), while the most recent is her first-ever photographic work, Athens, made in 2024.

The title of the exhibition, The Giddy Road to Ruin, derives from her 2015 painting of the same name and may be interpreted as a reflection of her thinking as well as the nature of painting itself. Displayed at the exhibition’s beginning and considered within the context of Greece’s ancient and modern landscape, the painting takes on greater significance, especially in relation to its presentation alongside the Athens (2024) collages. In these graphic images we experience the echoes and rumblings of both the present and history.

Charline von Heyl is one of the most significant painters of her generation. Educated in Germany in the 1980s and inspired by both senior artists and contemporaries—including Martin Kippenberger, Rosemarie Trockel, and Michael Krebber, as well as Albert Oehlen, Jutta Koether, and Cosima von Bonin—her work began to carve out new territory, particularly after her move to New York in 1996. While her paintings share the rigor and intensity of theirs, von Heyl’s work eschews irony in favor of a more openly amused humor and a certain nimbleness in the synthesis of mind and hand.

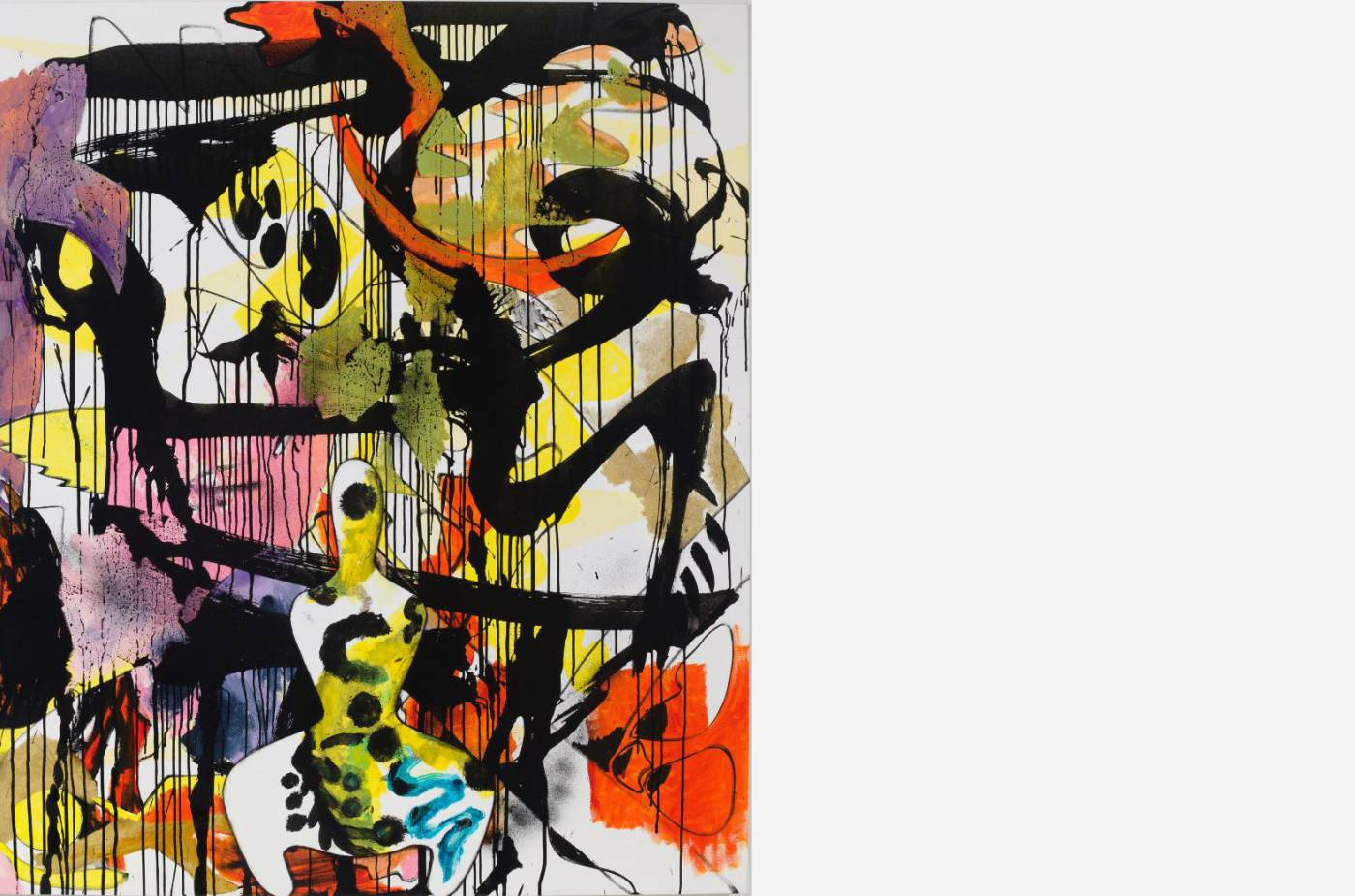

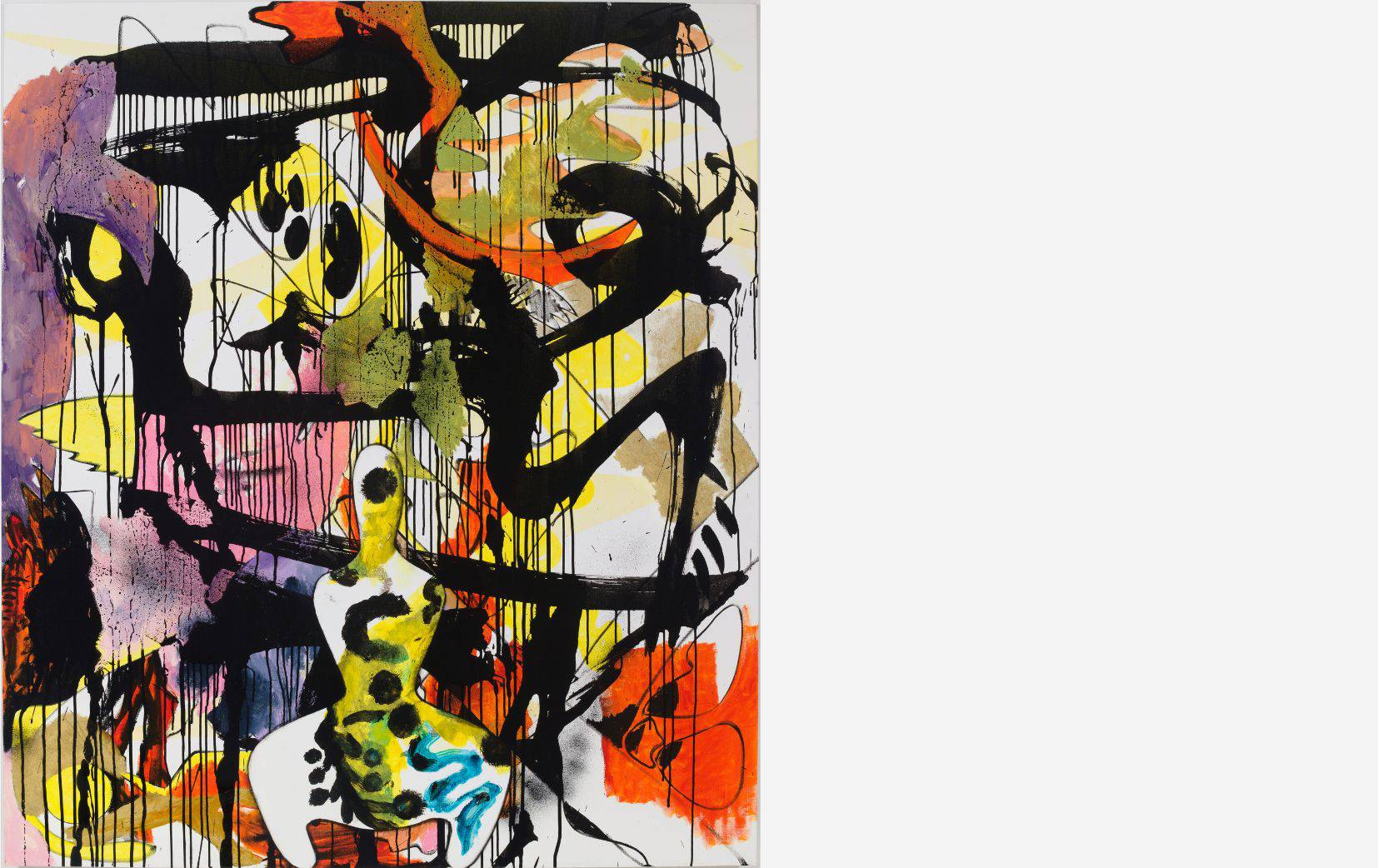

Once in the United States, von Heyl developed a novel, constructive, and strategic approach to creating and solving artistic problems that allows each painting to be “a self-generating machine that finds its own soul.” Her work is neither wholly abstract nor representational but simultaneously both. Her art succeeds by embracing visual and conceptual contradictions, keeping viewers intrigued by the seemingly impossible combinations of subjects, compositions, and styles that result in deeply satisfying yet puzzling works. In many of her paintings, forms appear both in stasis and in flux simultaneously, as evident in works such as Demons Dance Alone (2022) or World Rabbit Clock (2022). Shapes seem to be concurrently at the fore and in the background, as seen in her depiction of bowling pins—a recurring image in her vocabulary, particularly well-represented in two paintings from 2015 on mid-twentieth-century barkcloth fabric that are located on the second floor of the exhibition. To the indiscriminate eye, the contradictory styles in von Heyl’s paintings might seem irreconcilable, yet they all coexist within the singularly coherent universe of her art.

While a series of four densely composed paintings on barkcloth are a through line from the first floor, the appearance of two stolid and iconic works on the second floor signal a change of mood in the exhibition. The heraldic devices in Untitled (11/93, I) (1993) carry ominous, even militaristic overtones, in contrast to the insouciant black-and-white cut-out shapes of Time Waiting (2010), which harken back to mid-century travel advertisements’ filtered interpretation of Cubism. These works stand in stark contrast to the owl paintings from 2020–2021, in which the generally solitary birds—symbols of good fortune and wisdom—gather, against type, into a multitude. This capacious theme, with its potential for great and even adorable variation, offered a lighthearted interlude for von Heyl to paint and for the viewer to enjoy encountering the third floor of the exhibition.

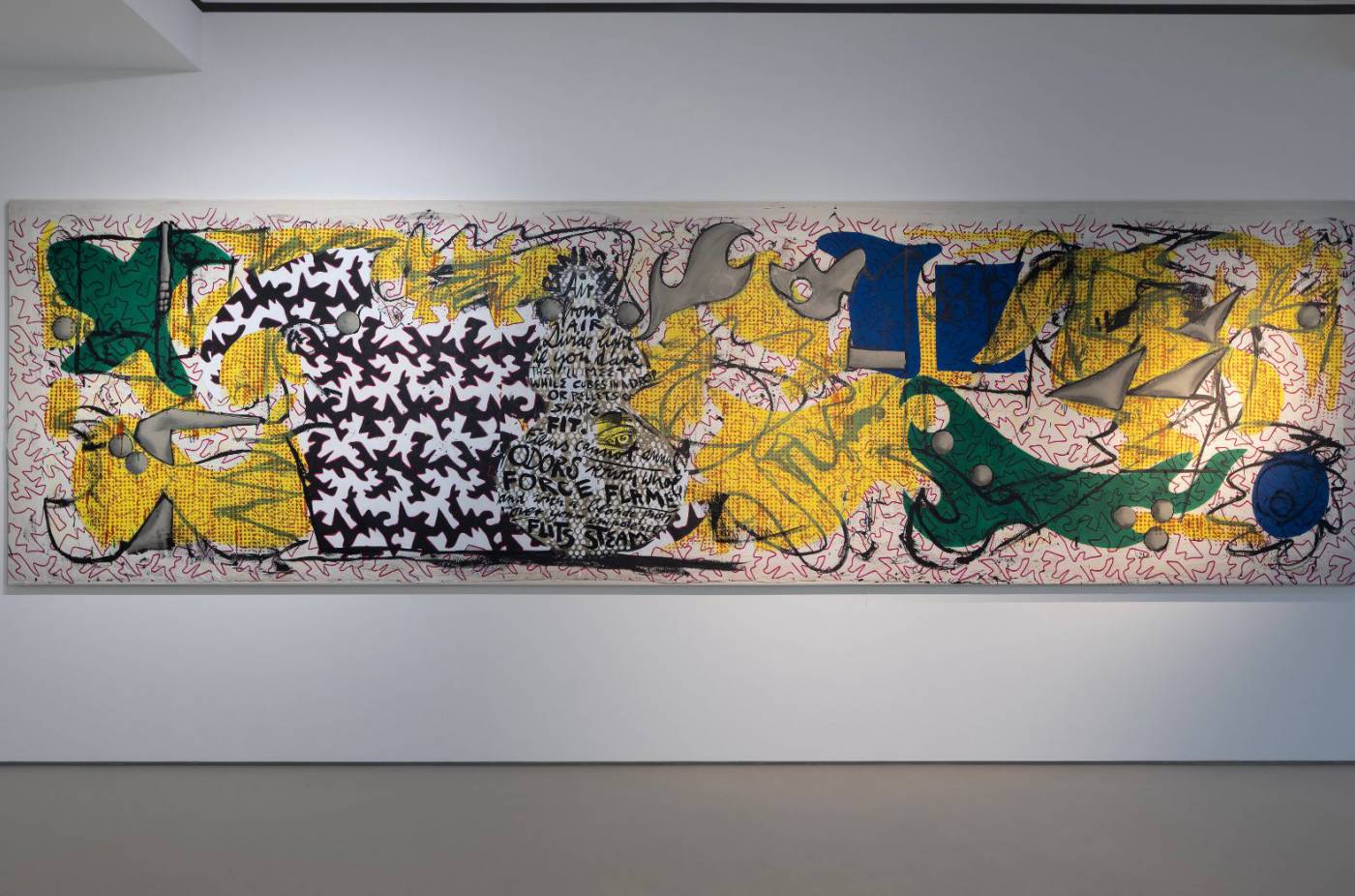

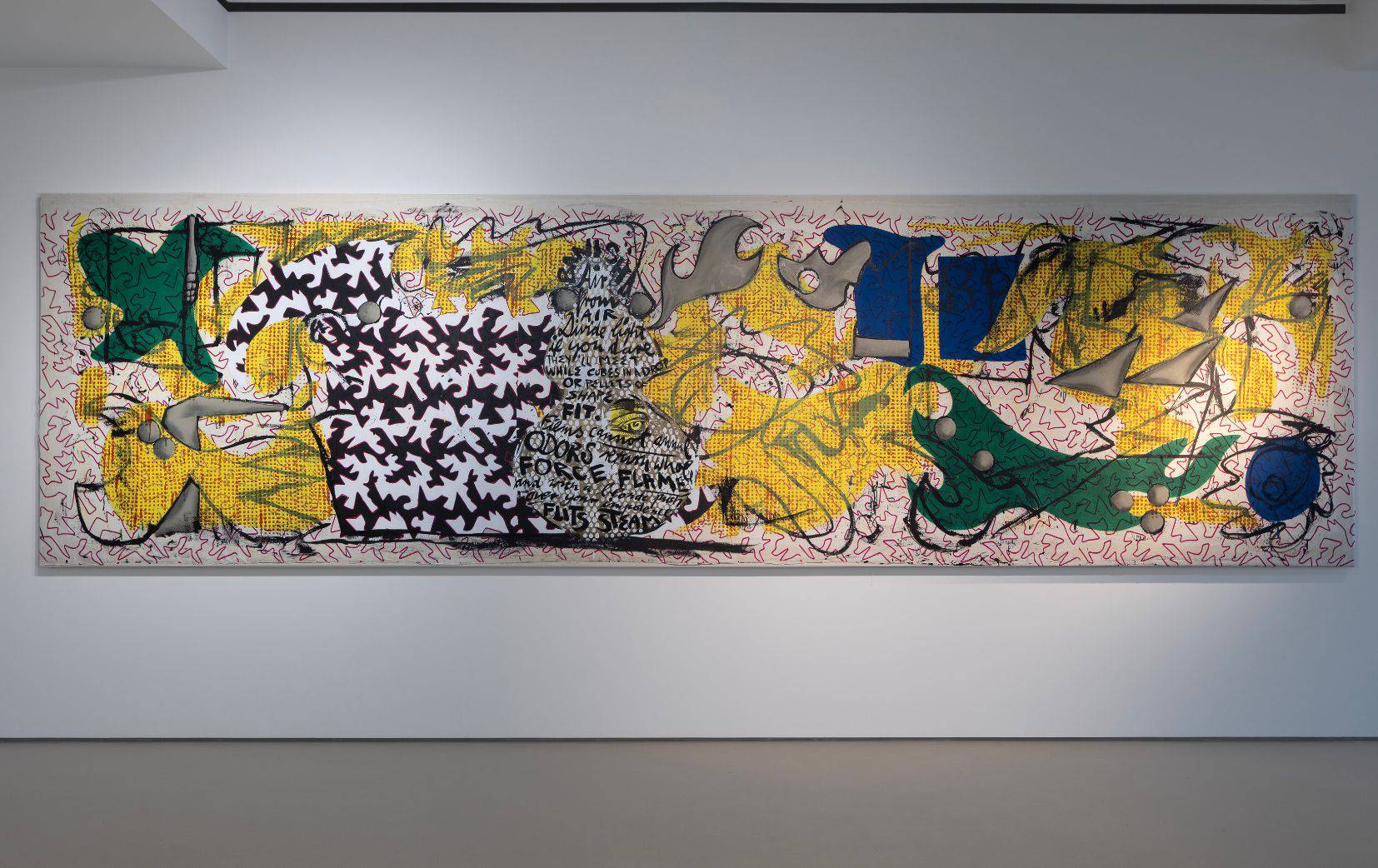

Here the opening salvo is a boldly blue bird in the large, rectangular painting Animal Delinquency (2021). Ultramarine fowl are partially obscured by two smudged-out, variegated forms of two other creatures—owls, perhaps? The collapse of subjects and the spaces they inhabit creates an apprehensive experience. The scroll-like structure of Banish Air from Air (2017) also features bird-like forms flying through interlocking patterns of words, lines, and shapes. At its center is a variation of her repeated, defiant yet playful female power figure, also seen in The Giddy Road to Ruin.

The painting Ninfa (2021) continues the subtle theme of feminine power in her work. Pulchritude is rendered as outlandish, with blue lips and a graceful line suggesting a chin overtaken by a coalescence of black and ochre biomorphic forms resembling birds. The head itself transforms into a dense field of patterns, becoming increasingly abstract. The fifteen diverse, rigorous while and whimsical black-and-white drawings that comprise Drawings Group 2 (2006) elaborate on and connect to the inscriptive elements—sometimes appearing as ideograms or Rorschach-like forms—not unlike Banish Air from Air. They also echo the structure and palette of the Athens Collages earlier in the exhibition. Each work on view is replete with such recursive connections, dissonances, and discontinuities—eye-opening and mind-boggling revelations await.

Charline von Heyl: The Giddy Road to Ruin is co-curated by Adam D. Weinberg and Skarlet Smatana, the director of The George Economou Collection, in close collaboration with the artist. A publication with essays by Weinberg and artist Helen Marten will accompany the exhibition.